A Persistent Human Hallucination

The stubborn belief that faster production and transmission of information brings global peace

The first Linotype machine in the U.S. was installed on July 1, 1886, at the Tribune newspaper in New York City. Invented by Ottmar Mergenthaler, a Linotype machine could produce five lines per minute compared to the one line per minute typically produced by typesetters.

Steven Lubar in InfoCulture: “Mark Twain, who lost a great deal of money investing in an automatic typesetting machine, suggested its value when he wrote that a Linotype ‘could work like six men and do everything but drink, swear, and go out on strike.’” A competitor to the Linotype, the Monotype, was invented in 1887 by Tolbert Lanston. It produced higher quality type and was controlled by a punched paper tape.

On July 7, 1752, Joseph-Marie Jacquard, French inventor of the Jacquard loom, was born. The Jacquard loom pioneered the use of punched tape or cards to give instructions to a machine, in this case, a loom weaving rugs and linens.

On July 9, 1836, Charles Babbage wrote in his notebook: “My notion is that cards (Jacquards) of the Calc. engine direct a series of operations and then recommence with the first so it might perhaps be possible to cause the same cards to punch others equivalent to any given number of repetitions. But their hole[s] might perhaps be small pieces of formulae previously made by the first cards.”

This passage, says Brian Randell in The Origins of Digital Computers, “puts beyond doubt the fact that Babbage had thought of using the Analytical Engine to what would today be described as ‘computing its own programs.’” In 1952, Arthur Samuel developed the first computer checkers playing program, the first to learn on its own, and in 1959, he coined the term “machine learning,” defining it as “programming of a digital computer to behave in a way which, if done by human beings or animals, would be described as involving the process of learning.”

In The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood, James Gleick quotes Edgar Allan Poe on Babbage’s machine: “What shall we think of an engine of wood and metal which can… render the exactitude of its operations mathematically certain through its power of correcting its possible errors?” and Oliver Wendell Holmes: “What a satire is that machine on the mere mathematician! A Frankenstein-monster, a thing without brains and without heart, too stupid to make a blunder; which turns out results like a corn-sheller, and never grows any wiser or better, though it grinds a thousand bushels of them!”

On July 1, 1890, two thousand clerks began processing the results of the 1890 U.S. Census, employing ninety-six of Herman Hollerith’s tabulating machines, using a punched card system where a hole punched in a specific place on the card signified a fact about an individual. The data collected on the population of the United States (62,947,714 in 1890) was processed in one year, compared to the eight years it took to process the 1880 Census.

On July 2, 1953, International Business Machines (IBM) announced the IBM 650, the world’s first mass-produced computer. The IBM 650 ran programs from punch cards and stored numbers up to ten digits long on a rotating magnetic drum. It dominated the computer market through the early sixties.

Kevin Maney in Making the World Work Better: “Hollerith gave computers a way to sense the world through a crude form of touch. Subsequent computing and tabulating machines would improve on the process, packing more information unto cards and developing methods for reading the cards much faster. Yet, amazingly, for six more decades computers would experience the outside way no other way.”

This was indeed “amazing,” since keyboards as input mechanisms were a century-plus-old invention. On July 23, 1829, William Austin Burt, a surveyor from Mount Vernon, Michigan, received a patent for the typographer, the earliest forerunner of the typewriter. On July 31, 1961, IBM introduced the IBM Selectric, replacing typebars and the moving carriage with a spherical printing element.

In 2006, a Boston Globe article described the fate of typewriters in the digital age: “When Richard Polt, a professor of philosophy at Xavier University, brings his portable Remington #7 to his local coffee shop to mark papers, he inevitably draws a crowd. ‘It’s a real novelty,’ Polt said. ‘Some of them have never seen a typewriter before … they ask me where the screen is or the mouse or the delete key.’”

On July 4, 1956, MIT researchers connected a keyboard to the Whirlwind computer as an experiment, demonstrating the feasibility of using keyboards for direct input. The Whirlwind was the first computer (1951) to operate in real time. One of the designers of the Whirlwind, Jay W. Forrester, was born on July 14, 1918. Forrester was also one of the inventors of magnetic-core memory, which remained the computer memory technology of choice until the early 1970s. In 1956, believing that all the major innovations in the field had been made, he moved to MIT’s business school, where he developed the field of system dynamics, computer modeling of complex systems, with applications in business and socioeconomics.

Punched cards were used as the primary input method for early computers until the keyboard replaced them. On July 4, 1971, Michael Hart, a freshman at the University of Illinois, entered the United States’ Declaration of Independence into the mainframe he was using, all in upper case, because there was no lower case yet on the mainframe’s keyboard. The first document in what will become Project Gutenberg was downloaded by six users. “I knew what the future of computing, and the internet, was going to be,” Hart later said.

What the expectations from the internet were going to be could have been learned from earlier reactions to the establishment of global networks.

On July 12, 1846, the New York Herald celebrated the inauguration of the telegraph line between Boston and New York: “When a telegraph network spanned the globe, war would be no more, and cannonballs and mortars would be locked up in museums as curiosities and remnants of a barbarous age.”

Ten years later, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote in English Traits: “Nations are getting obsolete, we go and live where we will. Steam has enabled men to choose what law they will live under. Money makes place for them. The telegraph is a limp band that will hold the Fenris Wolf of war. For now, that a telegraph line runs through France and Europe, from London, every message it transmits makes stronger by one thread, the band which war will have to cut.”

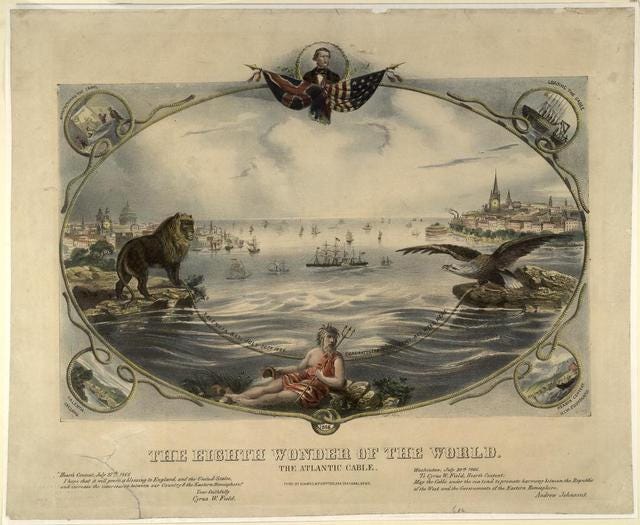

On July 27, 1866, the installation of the Atlantic Cable, connecting the U.S. with Europe, was completed. The first working cable, completed in 1858, failed within a few weeks. Before it did, however, it prompted the biggest parade New York had ever seen and accolades that described the cable, as one newspaper said, as “next only in importance to the ‘Crucifixion.’”

Steven Lubar in InfoCulture: “For merchants, fresh news meant the difference between profit and loss… Information was the key, and more and fresher information was better. These merchants lived in an Information Age. Their hopes and fears and expectations and beliefs about the new information technology were, in some ways, not too far removed from ours.”

Tom Standage in The Victorian Internet: “The hype soon got going again once it became clear, that this time, the transatlantic link was here to stay… [The cable] was hailed as ‘the most wonderful achievement of our civilization’… Edward Thornton, the British ambassador, emphasized the peacemaking potential of the telegraph. ‘What can be more likely to effect [peace] than a constant and complete intercourse between all nations and individuals in the world?’ He asked.

Ever since, the belief that global networks of any kind can abolish war and topple tyrants has stubbornly persisted:

“The Dell Theory of Conflict Prevention argues that no two countries that are both part of the same global supply chain will ever fight a war as long as they are each part of that supply chain” –Thomas Friedman, The World Is Flat, 2005

“This generation will determine if the world can avoid the apocalypse that will come if the fear-ridden establishments continue to dominate global politics, motivated by terror, armed with nukes, and playing old but now far too dangerous games. This generation will not bypass existing institutions and methods: look at the record turnout in Iran and the massive mobilization of the young and minority vote in the US. But they will use technology to displace old modes and orders” –Andrew Sullivan, “The Revolution Will Be Twittered,” The Atlantic Monthly, June 13, 2009

“We live at a moment when the majority of people in the world have access to the internet or mobile phones—the raw tools necessary to start sharing what they're thinking, feeling and doing with whomever they want. …By giving people the power to share, we are starting to see people make their voices heard on a different scale from what has historically been possible. These voices will increase in number and volume. They cannot be ignored. Over time, we expect governments will become more responsive to issues and concerns raised directly by all their people rather than through intermediaries controlled by a select few”—Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s IPO filing, 2012

A more accurate description of the “information age” and the actual impact of the internet is found in New Yorker cartoons. On July 5, 1993, Peter Steiner’s cartoon declared, “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.” A dozen years later, another cartoon depicted two dogs discussing contemporary conversations: “I had my own blog for a while, but I decided to go back to just pointless, incessant barking.”