Artificial Intelligence (AI) Is So 1955

The quintessential brain looked very much like an opaque, featureless bladder

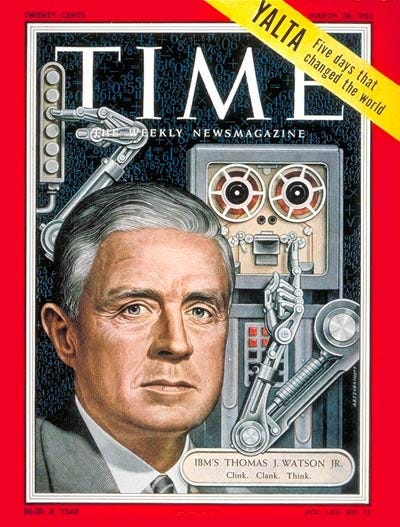

Today in 1955, Time Magazine published the cover story “Brain Builders”:

"At last I came under a huge archway and beheld the Grand Lunar exalted on his throne in a blaze of incandescent blue . . . The quintessential brain looked very much like an opaque, featureless bladder with dim, undulating ghosts of convolutions writhing visibly within . . . Tiers o…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to This Month In the History of Information Technologies to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.