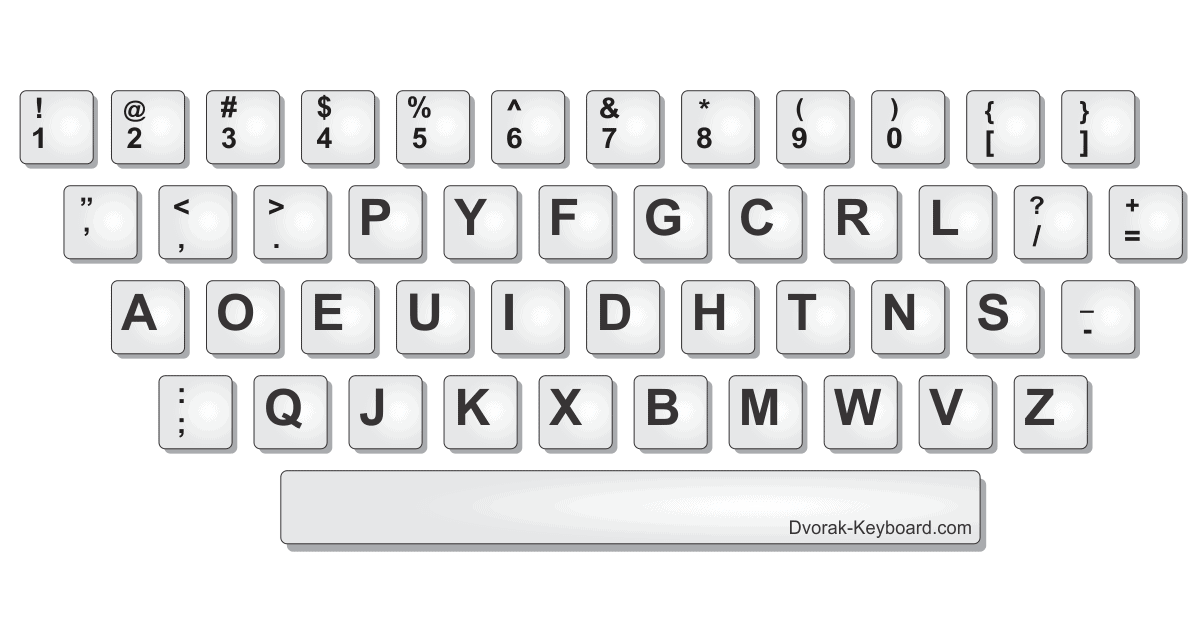

Today in 1936, August Dvorak and William Dealey received a patent for the Dvorak typewriter keyboard (US No. 2,040,248).

Dvorak and Dealey designed keyboard in a manner which would increase a user’s typing speed by placing the keys of common letters on the home row and within reach of the dominant fingers of the hands. The failure of the Dvorak keyboard to gain traction in the market (presumably because of the switching costs for companies and typists used to the QWERTY keyboard) has been frequently cited as an example of “market failure.”

Economists Stan Liebowitz and Stephen E. Margolis, however, have written extensively on the subject, arguing in “The Fable of the Keys” specifically with economic historian Paul David. They assert that there is little evidence for the actual superiority of the Dvorak layout over Qwerty and that the historical record shows that in the competitive conditions of the typewriter market at the time, “a keyboard offering significant advantages” could have succeeded.

Liebowitz and Margolis use what they found about this “market failure” episode to further explain what’s wrong with the thinking of most economists:

There is more to this disagreement than a difference in the evidence that was revealed by our search of the historical record. Our reading of this history reflects a more fundamental difference in views of how markets, and social systems more generally, function. David's overriding point is that economic theory must be informed by events in the world. On that we could not agree more strongly. But ironically, or perhaps inevitably, David's interpretation of the historical record is dominated by his own implicit model of markets, a model that seems to underlie much economic thinking. In that model an exogenous set of goods is offered for sale at a price, take it or leave it. There is little or no role for entrepreneurs. There generally are no guarantees, no rental markets, no mergers, no loss-leader pricing, no advertising, no marketing research. When such complicating institutions are acknowledged, they are incorporated into the model piecemeal. And they are most often introduced to show their potential to create inefficiencies, not to show how an excess of benefit over cost may constitute an opportunity for private gain.

In the world created by such a sterile model of competition, it is not surprising that accidents have considerable permanence. In such a world, embarking on some wrong path provides little chance to jump to an alternative path. The individual benefits of correcting a mistake are too small to make correction worthwhile, and there are no agents who might profit by devising some means of capturing a part of the aggregate benefits of correction.