AI: An Offbeat History, my other newsletter, could be of interest to you, dear subscriber

On May 1, 1957, the film Desk Set was released. “They can’t build a machine to do our job; there are too many cross-references in this place,” the head librarian (Katharine Hepburn) tells her anxious colleagues in the research department when a “methods engineer” (Spencer Tracy) is hired to “improve workman-hour relationship” in a large corporation. By the film’s end, she proves her point by winning, not only the engineer’s heart, but also a contest with the ominous-looking EMERAC, a room-sized “electronic brain” (aka a computer).

The film, particularly the statement about cross-references, has been a source of inspiration and a rallying cry for librarians ever since. I learned about it when, in 1988, I joined the corporate research department (which was part of a magnificent network of libraries) at Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), a leading purveyor of “electronic brains. "

In 2002, Cheryl Knott Malone published an article on Desk Set in the IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, calling it “the lone film [at the time] to offer a vision of the future of computing outside the realm of science fiction.” The film was “prophetic in its depiction of automated information retrieval by an electronic computer capable of storing the contents of an entire library, processing natural-language input, and prompting users to formulate more precise queries.”

More broadly, I would argue, Desk Set was about the promise and threat of new technology, its perceived potential to mimic (and replace) the human brain. That meant not only being able to think and reason like human beings but also suffering from similar memory lapses and the failure of overworked circuits.

By anthropomorphizing the computer (called “Emmy” by the engineers working with it), the movie puts the fears of the new technology to rest. After all, it is fallible, and it certainly cannot replace the librarians; it can only assist with mechanical, repetitive work, such as processing the payroll. That depiction of the computer was in the interest of IBM, which sponsored the film, and its attempts at the time to quiet down the growing anxiety of its customers and their trepidation about the new “artificial intelligence.”

However, the anxiety about the new technology did not go away. In surveying librarians’ attitudes in the 1950s and later, Malone quotes Jesse Shera, dean of the library school at Western Reserve University and one of the first proponents of the synergy between information science and library science. Shera was the chief sponsor of The Librarian and the Machine, written in the early 1960s (published 1965) by Paul Wasserman, a study of the “promise and threat” of computers in libraries.

The book opens with the following declaration: “As if it were not already a problem enough for library administrators striving to respond to the myriad pressures and infinite complexities…. A newer and even more foreboding terror [my italics]… was beginning to emerge more clearly. I refer to the computer and its attendant supporting apparatus.” But, like Desk Set, his conclusion at the end of his year-long study is comforting: “Machines today can do much of man’s work more rapidly and efficiently; but they cannot do his intellectual work as well.”

Do ChatGPT and other Large Language Models or LLMs present a new reality in which computers, like the fictional EMERAC, finally manage to “converse” with their users? Do they succeed in prompting them to formulate more precise queries? How much of man’s “intellectual work” (and at what quality) can AI do today and what tasks and jobs will it replace in the future?

A few years before the first “electronic brains” started automating work, Fremont Rider, Wesleyan University Librarian, published The Scholar and the Future of the Research Library (1944). He estimated that American university libraries were doubling in size every sixteen years. Given this growth rate, Rider speculated that the Yale Library in 2040 will have “approximately 200,000,000 volumes, which will occupy over 6,000 miles of shelves… [requiring] a cataloging staff of over six thousand persons.”

That was somewhat similar to the prediction made in the 1930s, when automatic telephone switchboards replaced operator-assisted switchboards, that before long, more operators would be needed than young girls suitable for the job.

That “prediction” served as a justification for automation, as AT&T had to explain to its customers why they were required to do the work previously performed by another human. Rider’s prediction about libraries and librarians was correct about the growth in the volume of knowledge stored on paper, but did not foresee that “electronic brains” would automate some knowledge-work and provide digital storage for the ever-growing volume of information. Most importantly, they will provide better means of finding relevant information, by librarians, and later, by anyone with access to the internet, a giant digital library.

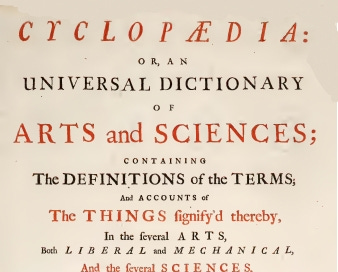

The quest to provide knowledge seekers with the knowledge they seek—and the links between one information item and another—is much older than the internet or the first computers. In 1728, Ephraim Chambers, a London globe-maker, published the Cyclopaedia, or, An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. It was probably the earliest attempt to link all the articles in an encyclopedia or, more generally, all the components of human knowledge by association. In the Preface, Chambers explained his innovative system of cross-references:

“Former lexicographers have not attempted anything like Structure in their Works; nor seem to have been aware that a dictionary was in some measure capable of the Advantages of a continued Discourse. Accordingly, we see nothing like a Whole in what they have done…. This we endeavoured to attain, by considering the several Matters [i.e., topics] not only absolutely and independently, as to what they are in themselves; but also relatively, or as they respect each other. They are both treated as so many Wholes, and so many Parts of some greater Whole; their Connexion with which, is pointed out by a Reference… A Communication is opened between the several parts of the Work; and the several Articles are in some measure replaced in their natural Order of Science, out of which the Technical or Alphabetical one had remov’d them.”

New concepts, like new technologies, raise questions about their assumed benefits and concerns about their presumed drawbacks. The supplement to the 1758 edition of the Cyclopaedia says:

Some few however condemn the use of all such dictionaries, on the first pretence, that, by lessening the difficulties of attaining knowledge, they abate our diligence in the pursuit of it; and by dazzling our eyes with superficial shew, seduce us from digging solid riches in the mine itself.

Regardless, the quest for better organization of information and knowledge continued. Just before the advent of “electronic brains,” Vannevar Bush wrote in As We May Think (1945): “Our ineptitude at getting at the record is largely caused by the artificiality of systems of indexing… Selection [i.e., information retrieval] by association, rather than by indexing may yet be mechanized.”

Will “electronic brains” help librarians or serve to replace them? Is ChatGPT a brilliant answer to Chambers’ attempt to create a knowledge-inquiry tool with the “Advantages of a continued Discourse”? Why was it—and still is—even conceivable that a computer can do man’s thinking, or more narrowly, replace a librarian? Because most of us fervently subscribe to the hallucination of “artificial general intelligence” or AGI, that computer engineers will develop (next year, we are told) a machine more intelligent than humans? Because of our “morbid fascination with the latest form of technology,” to use another Wasserman observation from 1965?

The organization I worked for when I joined DEC in 1988 had not only reference librarians and lots of paper-based knowledge but also some digitized information. A team of information retrieval (what we started calling “search” ten years later) experts developed and managed a database of digitized news articles (“competitive information system” or CIS). Among other innovations, they developed database search software—what we today call “AI”—that could distinguish between “DEC” as the company’s name and “Dec” as an abbreviation for December.

In those days, the information retrieval world was ruled by “taxonomies” and “ontologies,” or attempts to organize information in hierarchies of concepts or categories, defining their relations. This paradigm was so strong that even later, in the early attempts to organize the rapidly growing information on the Web, the first “search engines” such as Yahoo! had a Chief Ontologist on staff.

Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the Web, troubled like Bush and Chambers before him by the way information was organized, was excited to escape from the “straightjacket of hierarchical documentation systems.” Berners-Lee wrote in Weaving the Web: “By being able to reference everything with equal ease, the web could also represent associations between things that might seem unrelated but for some reason did actually share a relationship.”

Google triumphed over taxonomy-obsessed Yahoo! and others because it got the true spirit of the Web. Google’s founders were the first to seize on Berners-Lee’s insight and build their information retrieval business on tracking closely cross-references (i.e., links between pages) as they were happening and correlate relevance with quantity of cross-references (i.e., popularity of pages as judged by how many other pages linked to them).

Chambers wrote about “the Advantages of a continued Discourse.” He meant the “conversation” between different concepts and themes, and how they relate. ChatGPT, and now “AI research agents,” speedily mine the vast troves of valuable, inaccurate, misleading, and outdated information on the Web. Just like the earlier “crowd-sourcing” perfected by Google, the clever mining of what people value and link to, these AI agents’ “reasoning” reflects how people ask questions online and search for information. Their “intelligence” is the sum of observations of online searches by thousands or millions of people and the information available, for better or worse, at any given moment on the Web. They simply regurgitate this summary; they can’t “converse” with the concepts or themes they find. Just like Chambers’ Cyclopaedia they are a helpful tool that requires human intelligence to make sense of, build upon, and create new (hopefully valuable) information and knowledge.