Network Effects

On the economic value of networked information

On November 1, 1870, the U.S. Weather Bureau made its first meteorological observations using reports from 24 locations, which were provided via telegraph. For the first time, weather observations from distant points could be “rapidly” collected, plotted, and analyzed at one location.

The Weather Bureau’s 1870 experiment was an early example of how the economic value of information increases when it’s networked, when information from one source is combined with information stored in another source, or when it is collected from disparate sources and stored in a single repository.

This potential increase in the economic value of networked information is often overlooked in what is known as the “network effect,” or the notion that a product or service becomes more valuable to its users as more people use it. This principle was first associated with the telephone—the larger the number of people owning telephones, the more valuable the telephone is to each owner. Since the emergence of a widely-used global network—the internet running the World Wide Web—it has been translated into a Silicon Valley mantra, ”get big fast,” prioritizing the acquisition of many non-paying customers over profits. It has been applied to all types of social networks and websites or apps catering to all internet users, with the growth in the number of “Monthly Active Users” (or weekly or daily) becoming the only metric used to value the success of online startups, and most recently, online AI chatbots such as ChatGPT.

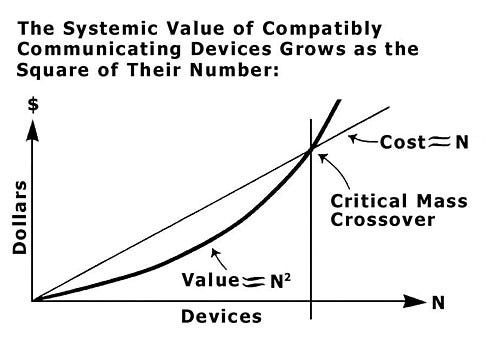

During the 1990s dot-com bubble, George Gilder popularized the concept of network effect as “Metcalfe’s Law.” Ethernet inventor Bob Metcalfe co-founded 3Com to develop and sell Ethernet cards. In 1983, answering his sales force’s need to convince customers that they should buy additional $1,000 Ethernet cards, he argued that “if a network is too small, its cost exceeds its value; but if a network gets large enough to achieve critical mass, then the sky’s the limit.” He even came up with a mathematical formulation, claiming that the value of a network is proportional to the square of the number of “compatibly communicating devices.”

That made sense in an era when there was not much information sent over the network and the motivation to connect PCs in a network was the economic benefit of sharing a printer rather than the sharing (and analysis) of information. Today, the economic benefit—of any network connecting people, organizations, and devices—lies in what is done with the information that is created and shared by all the “nodes” of the network.

Hear are a few November milestones in the history of networked information:

On November 13, 1990, Tim Berners-Lee published what came to be known as “the world’s first web page,” marking the birth of the global network that made information sharing the focal point of increasing economic value.

As he recounted in Weaving the Web, Berners-Lee started developing in November 1990 “a client program—a point-and-click browser/editor—which I just called WorldWideWeb… I started the global hypertext Web page, on the info.cern.ch server, with my own notes, specifications of HTTP, URI, and HTML, and all the project-related information… At long last I could demonstrate what the Web would look like.”

Almost a decade later, a college student realized that people worldwide could use this global network to share their personal repositories of digital music. On November 17, 1999, Slashdot, the “News for Nerds. Stuff that Matters” website, reported: “There is a cool new tool out there called Napster that allows anyone to become a publicly accessible FTP site – tapping into that huge resource of personal MP3 collections that everyone has, but have not been able to share… RIAA [Recording Industry Association of America] should be scared out of their minds because users are not logged on permanently, so it’s hard to track them down to take legal action.” The RIAA filed a lawsuit against Napster on December 7, 1999, and, as a result, the service shut down in July 2001.

Using the Web for transforming the exchange of physical goods (in addition to digital ones), however, has made the most significant impact on the economy. A crucial aspect of the success of e-commerce, and especially of Amazon in its early days, was the exchange of information not just about the products sold, but also between buyers, in the form of reviews.

On November 21, 2005, Cyber Monday was born with Shop.org announcing in a press release, “‘Cyber Monday’ Quickly Becoming One of the Biggest Online Shopping Days of the Year.” According to Shop.org/BizRate Research 2005 eHoliday Mood Study, 77% of online retailers said that their sales “increased substantially” the previous year on the Monday after Thanksgiving.

The information sent on networks is not always beneficial to the multitude receiving it. Call it Negative Network Effects. On November 3, 1983, Fred Cohen, a student at the University of Southern California School of Engineering, conceived of the first computer virus, or the spreading of an infected host file, as an experiment to be presented at a weekly seminar on computer security. Four years later, Cohen demonstrated that no algorithm can perfectly detect all possible viruses.

On November 2, 1988, Robert T. Morris, a computer science graduate student at Cornell University, released a self-replicating computer worm on ARPANET (a predecessor of the internet). The worm was part of a research project meant to determine the size of the internet by infecting UNIX systems in order to count the number of existing connections. As a result of a programming error, the worm began infecting machines repeatedly, causing clogged networks and system crashes. It became the first worm to spread extensively “in the wild,” the first worm to receive extensive media coverage, and one of the first programs to exploit a buffer overrun vulnerability. Morris was dismissed from Cornell, sentenced to three years’ probation, and fined $10,000. He eventually became a tenured professor at MIT.

Cohen and Morris were known at the time as “hackers,” godfathers of today’s $285 billion cybersecurity market. On November 20, 1963, the MIT student newspaper reported that many telephone services had been curtailed “because of so-called hackers,” the earliest known public use of the term.

According to Steven Levy in Hackers, members of MIT’s Tech Model Railroad Club in the late 1950s used the term a hack to describe “a project undertaken or a product built not solely to fulfill some constructive goal but with some wild pleasure taken in mere involvement… The most productive people working on the S&P [the Signals and Power Subcommittee of the club] called themselves ‘hackers’ with great pride.”

The 1963 article in The Tech described some of the wild, pleasure-filled projects:

The hackers have accomplished such things as tying up all the tie-lines between Harvard and MIT, or making long-distance calls by charging them to a local radar installation. One method involved connecting the PDP-1 computer to the phone system to search the lines until a dial tone, indicating an outside line, was found…. To quote one accomplished hacker, “the field is always open for experimentation.”

Constant experimentation has led to increasingly larger quantities of information being sent over networks and collected in vast data pools. “Big Data” and its statistical analysis—“Data Science”—became the New New Thing, quickly to be replaced by “AI.” It turned out that computers learn much better from examples with the right “deep learning” algorithms, but most importantly, with vast quantities of data and an extensive amount of computer processing power. The network effect became a new mantra—“at scale,” and “scaling laws,” the mathematical proof, as valid as “Metcalfe’s Law,” of the eventual arrival of “superintelligent” machines. I would venture to guess that the economic value of networked information or AI will manifest itself not in robots keeping humans as pets, but in computers augmenting human intelligence and assisting (or intruding) in all manner of human activity, just as they have done for the last seven-plus decades.