The Machine of Our Times

The past and present of automation, augmentation, and “democratization”

This month’s milestones in the history of information technologies highlight the role of mechanical devices in automating work, augmenting or replicating human activities, and allowing many people to participate in previously highly specialized endeavors—a process technology vendors like to call “democratization.”

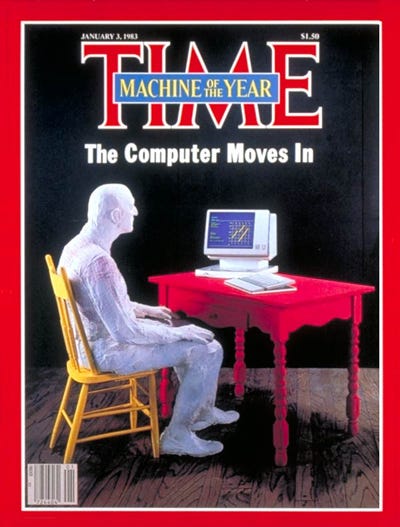

On January 3, 1983, Time magazine put the PC on its cover as “machine of the year.” Time’s publisher John A. Meyers: “Several human candidates might have represented 1982, but none symbolized the past year more richly, or will be viewed by history as more significant, than a machine: the computer.”

The Time magazine cover appeared just a few years after the arrival of the first PCs and the development of software that automated previous work and expanded its scope to include non-specialists. For example, turning some accounting work—specifically, management accounting, the ongoing internal measurement of a company’s performance—into a task that employees without an accounting degree could accomplish. This “democratization” of accounting not only automated previous work but greatly augmented management work, giving business executives easy access to data about their companies and new ways to measure and predict future performance.

On January 2, 1979, Software Arts was incorporated by Dan Bricklin and Bob Frankston to develop VisiCalc, the world’s first electronic spreadsheet program. VisiCalc came to be widely regarded as the first “killer app” that turned the PC into a serious business tool. Dan Bricklin:

The idea for the electronic spreadsheet came to me while I was a student at the Harvard Business School, working on my MBA degree, in the spring of 1978. Sitting in Aldrich Hall, room 108, I would daydream. "Imagine if my calculator had a ball in its back, like a mouse..." (I had seen a mouse previously, I think in a demonstration at a conference by Doug Engelbart, and maybe the Alto). And "...imagine if I had a heads-up display, like in a fighter plane, where I could see the virtual image hanging in the air in front of me. I could just move my mouse/keyboard calculator around on the table, punch in a few numbers, circle them to get a sum, do some calculations, and answer '10% will be fine!'" (10% was always the answer in those days when we couldn't do very complicated calculations...)

In the summer of 1978, between the first and second year of the MBA program, while riding a bike along a path on Martha's Vineyard, I decided that I wanted to pursue this idea and create a real product to sell after I graduated.

Bricklin understood the potential of the “democratization” and automation of accounting, of eliminating ledgers that required specialized skills and manual recalculation of the entire spreadsheet when a single item changed.

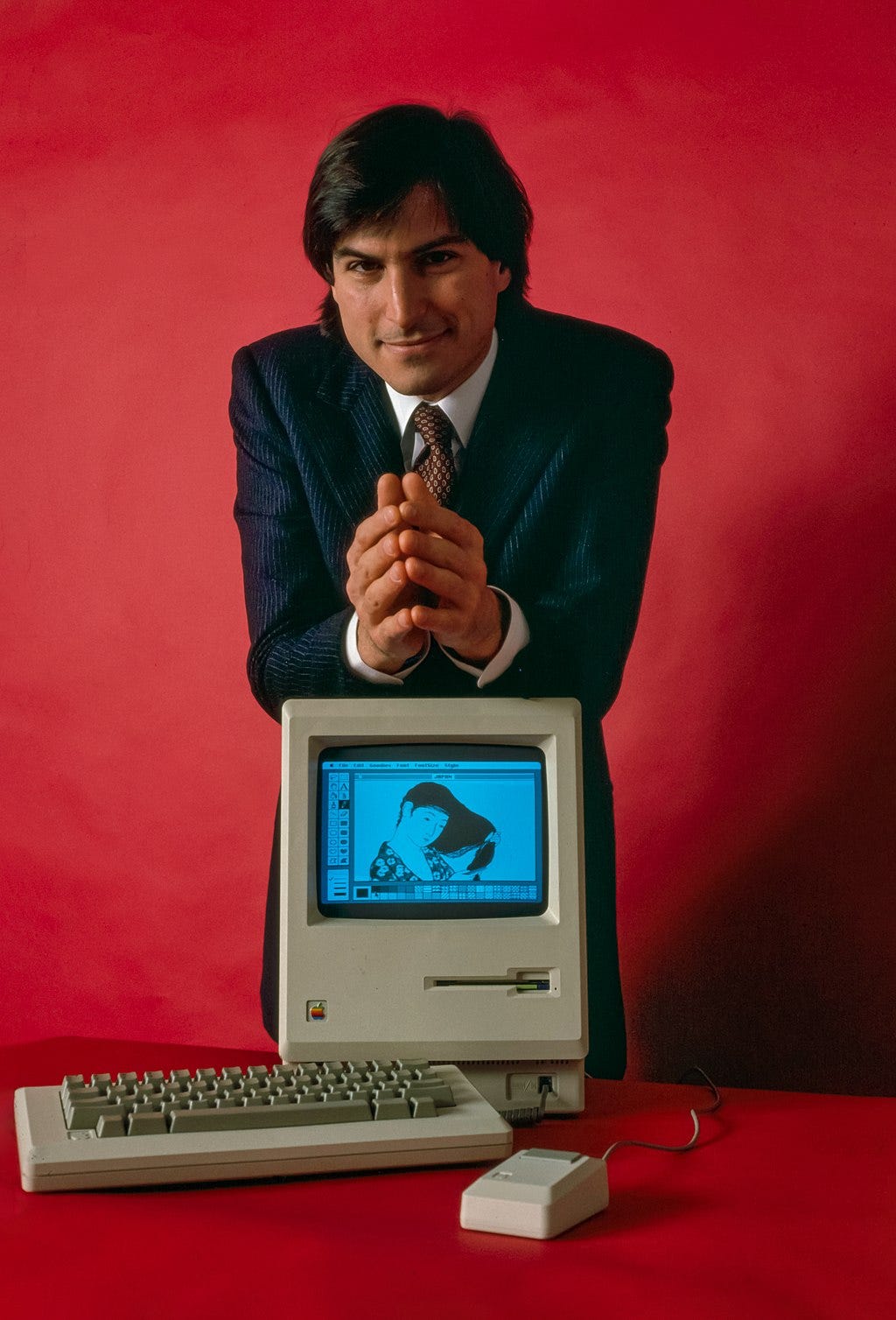

Steve Jobs knew how to exploit the marketing potential of the “democratization” of computing. On January 22, 1984, the Apple Macintosh was introduced with the "1984" television commercial which aired during Super Bowl XVIII. The commercial was later called by Advertising Age “the greatest commercial ever made.” A few months earlier, before showing a preview of the commercial, Steve Jobs said:

It is now 1984. It appears IBM wants it all. Apple is perceived to be the only hope to offer IBM a run for its money. Dealers initially welcoming IBM with open arms now fear an IBM dominated and controlled future. They are increasingly turning back to Apple as the only force that can ensure their future freedom. IBM wants it all and is aiming its guns on its last obstacle to industry control: Apple. Will Big Blue dominate the entire computer industry? The entire information age? Was George Orwell right about 1984?

Following the airing of the “1984” TV commercial, the Macintosh was launched on January 24, 1984. It was the first mass-market personal computer featuring a graphical user interface and a mouse, offering two applications, MacWrite and MacPaint, designed to show off its innovative interface. By April 1984, 50,000 Macintoshes were sold.

Steven Levy announced in Rolling Stones “This [is] the future of computing.” Levy quoted Steve Jobs: “I don't want to sound arrogant, but I know this thing is going to be the next great milestone in this industry. Every bone in my body says it's going to be great, and people are going to realize that and buy it.” And Mitch Kapor, developer of Lotus 1-2-3, a best-selling spreadsheet program for the IBM PC: “The IBM PC is a machine you can respect. The Macintosh is a machine you can love.”

When Steve Jobs introduced the Macintosh, the Mac said: “Never trust a computer you cannot lift.”

On January 24, 1984 (give or take a day or two), I started working for NORC, a social science research center at the University of Chicago. Over the next year, I experienced firsthand the shift from large, centralized computers to personal ones and the move from a command line to a graphical user interface.

My responsibilities included managing $2.5 million in survey research budgets. At first, I used the budget management application running on the University’s VAX mini-computer (mini, as opposed to mainframe). I would log on using a remote terminal, type some commands, and enter the new numbers I needed to record. Then, after an hour or two of hard work, I pressed a key on the terminal, ordering the VAX to re-calculate the budget with the new data I entered. To this day, I remember my great frustration and dismay when the VAX responded by indicating something was wrong with the data I entered. Telling me what exactly was wrong was beyond what the VAX—or any other computer program at that time—could do (this was certainly true in the case of the mini-computer accounting program I used).

I had to start the work from the beginning and hope that on the second or third try, I will get everything right and a new budget spreadsheet will be created. This, by the way, was no different from my experience working for a bank a few years before, where I totaled by hand the transactions for the day on an NCR accounting machine. Quite often I would get to the end of the pile of checks only to find out that the accounts didn’t balance because somewhere I entered a wrong number and I would have to enter all the data again.

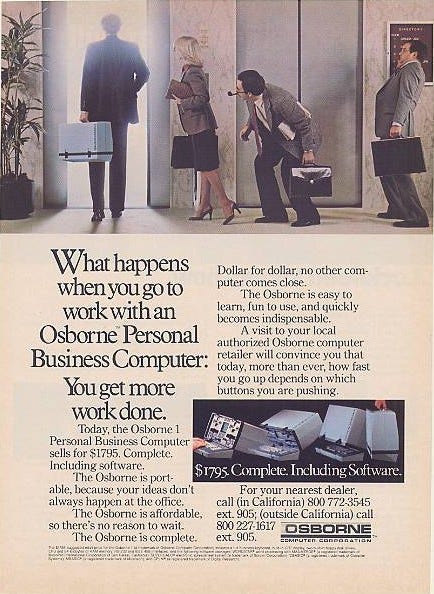

Visicalc changed forever this linear approach to accounting. At NORC, I benefited from that idea when I started managing budgets with Visicalc, running on an Osborne laptop. Soon thereafter I migrated to an IBM PC which ran the invention of another HBS student, Mitch Kapor, who was also frustrated with re-calculation and other delights of paper-based accounting or electronic spreadsheets running on large computers.

Lotus 1-2-3 was an efficient tool for managing budgets that managers could use themselves without wasting time on figuring out what data entry mistake they made or waiting for the accounting department to deliver the goods. Now they had complete control of the processing of the data, to say nothing, of course, about modeling or what-if scenarios, the entire range of budgeting and forecasting functions at their fingertips.

The role of managers in the “PC revolution” serves as an illustration of how the way people use new technology and how they perceive it is as important as the technology itself. Cloudy crystal balls or failed predictions about information technologies suffer from ignoring humans—their motivations, aspirations, attitudes—and ignoring how society works.

The best example of such failure I’m familiar with is “The Office of the Future,” a report published in 1976 by the Long-Range Planning Service of the Stanford Research Institute (SRI). The manager of 1985, the report predicted, will not have a personal secretary. Instead, he (decidedly not she) will be assisted, along with other managers, by a centralized pool of assistants (decidedly and exclusively, according to the report, of the female persuasion). He will contact the “administrative support center” whenever he needs to dictate a memo to a “word processing specialist,” find a document (helped by an “information storage/retrieval specialist”), or rely on an “administrative support specialist” to help him make decisions.

Unlike many similar forecasts, this report does consider sociological factors, in addition to organizational, economic, and technological trends. But it could only see what was in the air at the time—the “women’s liberation” movement—and it completely missed its future implications: “Working women are demanding and receiving increased responsibility, fulfillment, and opportunities for advancement. The secretarial position as it exists today is under fire because it usually lacks responsibility and advancement potential… In the automated office of the future, repetitious and dull work is expected to be handled by personnel with minimal education and training. Secretaries will, in effect, become administrative specialists, relieving the manager they support of a considerable volume of work.”

Regardless of the women’s liberation movement of his day, the author could not see beyond the creation of a 2-tier system in which some women would continue to perform dull and unchallenging tasks, while other women would be “liberated” into a fulfilling new job category of “administrative support specialist.” In this 1976 forecast, there are no women managers.

But this is not the only sociological factor the report missed. The most interesting sociological revolution of the office in the 1980s – and one missing from most accounts of the PC revolution – is what managers (male and female) did with their new word processing, communicating, and calculating machine. They took over some of the “dull” secretarial tasks that no self-respecting manager would deign to perform before the 1980s.

This was the real revolution: The typing of memos (later emails), the filing of documents, the creation of more and more data in digital form. In short, a large part of the management of office information, previously exclusively in the hands of secretaries, became in the 1980s (and progressively more so in the 1990s and beyond) an integral part of managerial work.

It was a question of status. No manager would type before the 1980s because it was perceived as work that was not commensurate with his status. Many managers started to type in the 1980s because now they could do it with a new “cool” tool, the PC, which conferred on them the leading-edge, high-status image of this new technology. (See the Osborne ad above). What mattered was that you were important enough to have one of these cool things, not that you performed with it tasks that were considered beneath you just a few years before.

Status matters. People matter. What we do with technology—and why and how—is an important factor in its adoption and its evolution.

Steve Jobs and the failed Lisa (introduced on January 19, 1983) and Macintosh teams changed that and gave us an interface that made computing easy, intuitive, and fun. NORC purchased 80 Macs when I worked there, mostly used for computer-assisted interviewing. I don’t think there was any financial software available for the Mac at the time and I continued to use Lotus 1-2-3 on the IBM PC. But I played with the Mac at any opportunity I got. Indeed, there was nothing like it at the time.

It took a few years before the software running on most PCs adapted to the new personal approach to computing, but eventually, Microsoft Windows came along and icons and folders ruled the day. Microsoft also crushed all other electronic spreadsheets with Excel and did the same to other pioneering word-processing and presentation tools. But Steve Jobs triumphed in the end with yet another series of innovations.

Introducing the iPhone on January 9, 2007, Jobs said:

Every once in a while, a revolutionary product comes along that changes everything… today, we're introducing three revolutionary products... The first one is a widescreen iPod with touch controls. The second is a revolutionary mobile phone. And the third is a breakthrough Internet communications device…. An iPod, a phone, and an internet communicator…These are not three separate devices, this is one device, and we are calling it iPhone.

Jobs should have said (or let the iPhone say): “Never trust a computer you cannot put in your pocket.” Or “Never trust a computer you cannot touch.” Today, he might have said, “Never trust a computer you cannot talk to.”

Explaining to the audience the new concept of “internet communicator,” Jobs mentioned email, browser, Google Maps, and detecting Wi-Fi. He did not mention and possibly had not envisioned what happened next: the widespread use of the iPhone (and the mobile phones that followed it) as a camera replacement.

Long before the invention of the PC and the iPhone, a new ingenious device was applied to the work of painters and illustrators, people with unique and rare skills for capturing and preserving reality.

On January 7, 1839, the Daguerreotype photography process was presented to the French Academy of Sciences by Francois Arago, a physicist and politician. Arago told the Academy that it was “…indispensable that the government should compensate M. Daguerre, and that France should then nobly give to the whole world this discovery which could contribute so much to the progress of art and science.”

On March 5, 1839, another inventor, looking (in the United States, England, and France) for government sponsorship of his invention of the telegraph, met with Daguerre. A highly impressed Samuel F. B. Morse wrote to his brother: “It is one of the most beautiful discoveries of the age… No painting or engraving ever approached it.”

In late September 1839, as Jeff Rosenheim writes in Art and the Empire City, shortly after the French government (on August 19) publicly released the details of the Daguerreotype process, “…a boat arrived [in New York] with a published text with step-by-step instructions for creating the plates and making the exposures. Morse and others in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia immediately set about to build their cameras, find usable lenses, and experiment with the new invention.”

New Yorkers were ready for the Daguerreotype, already alerted to the “new discovery” by articles in the local press, such as the one in The Corsair on April 13, 1839, titled “The Pencil of Nature”: “Wonderful wonder of wonders!! … Steel engravers, copper engravers, and etchers, drink up your aquafortis, and die! There is an end to your black art… All nature shall paint herself — fields, rivers, trees, houses, plains, mountains, cities, shall all paint themselves at a bidding, and at a few moment’s notice.”

In 1838, Charles Wheatstone invented the first mass-produced photographic images, the stereographs, a pair of photographs mounted side-by-side that create the illusion of a three-dimensional image when viewed through a stereoscope. In “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph” (The Atlantic Monthly, June 1859), Oliver Wendell Holmes captured the wonders of photography in yet another memorable phrase, “the mirror with a memory”:

The Daguerreotype… has fixed the most fleeting of our illusions, that which the apostle and the philosopher and the poet have alike used as the type of instability and unreality. The photograph has completed the triumph, by making a sheet of paper reflect images like a mirror and hold them as a picture… [it is the] invention of the mirror with a memory…

The time will come when a man who wishes to see any object, natural or artificial, will go to the Imperial, National, or City Stereographic Library and call for its skin or form, as he would for a book at any common library… we must have special stereographic collections, just as we have professional and other special libraries. And as a means of facilitating the formation of public and private stereographic collections, there must be arranged a comprehensive system of exchanges, so that there may grow up something like a universal currency of these bank-notes, or promises to pay in solid substance, which the sun has engraved for the great Bank of Nature.

Let our readers fill out a blank check on the future as they like—we give our indorsement to their imaginations beforehand. We are looking into stereoscopes as pretty toys, and wondering over the photograph as a charming novelty; but before another generation has passed away, it will be recognized that a new epoch in the history of human progress dates from the time when He who

never but in uncreated light

Dwelt from eternity—took a pencil of fire from the hand of the “angel standing in the sun,” and placed it in the hands of a mortal.

“Daguerreotypes introduced to Americans a new realism, a style built on close observation and exact detail, so factual it no longer seemed an illusion,” William Howarth painted in Civilization (March/April 1996) the larger picture of a newly born industry in America: “Hawthorne’s one attempt at literary realism, The House of the Seven Gables (1851), features a daguerreotypist who uses his new art to dispel old shadows: ‘I make pictures out of sunshine,’ he claims, and they reveal ‘the secret character with a truth that no painter would ever venture upon.’… By 1853 the American photo industry employed 17,000 workers, who took over 3 million pictures a year.”

A hundred and fifty years after what Holmes called the moment of the “triumph of human ingenuity,” the Metropolitan Museum of Art mounted an exhibition on the early days of Daguerreotypes in France. Said Philippe de Montebello, the director of the museum at the time: “The invention of the daguerreotype—the earliest photographic process—forever altered the way we see and understand our world. No invention since Gutenberg’s movable type had so changed the transmission of knowledge and culture, and none would have so great an impact again until the informational revolution of the late twentieth century.”

In the same year of the Metropolitan’s exhibition, 2003, more digital cameras than traditional film cameras were sold for the first time in the U.S. The “informational revolution” has replaced analog with digital, and digital images captured by smartphones and shared on the internet have animated the triumph of Deep Learning (shortly to be renamed “AI”) at the ImageNet competition of 2012, ushering in a new—and so far very successful and quite “democratic”—stage in the evolution of “artificial intelligence.” Today’s worldwide “Stereographic Library,” the Web, supplied the labeled images needed to “train” a computer to identify and categorize objects, people, places, text, and actions in digital images and videos, in a wide range of domains from healthcare to banking to nature.

But these innovations—and the new image identification proficiency of computers—did not alter the idea of photography as invented by Nicéphore Niépce in 1822, and captured so well by the inimitable Ambrose Bierce in his definition of “photograph” (The Devil’s Dictionary, 1911): “A picture painted by the sun without instruction in art.”