Turing Saw the Future of Computing

Storage more important than speed

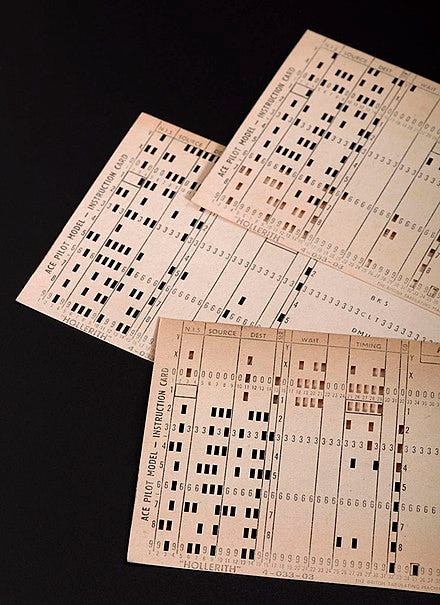

Today in 1947, Alan Turing presented to the London Mathematical Society a detailed description of the Automatic Computing Engine (ACE), an early British stored-program computer.

In addition to explaining how the ACE worked, Turing touched in his presentation on other topics that are much discussed today, such as the impact of computers on jobs and the question of machine intelligence. But for today’s episode of this newsletter, I’ll focus on computer data storage.

In Alan Turing: His Work and Impact (2013), Anthony Beavers introduces Turing’s lecture by connecting it to the “industrialization of information” of the 19th century, noting that Turing “does not show a a clean break that starts a new era but strong attachment to the preceding one.” Beavers makes clear what made digital computers different from the information devices of the past: “Edison, Bell, and several others could store information and move it around. They could not, however, capture it temporarily in a memory store, process it, and then produce a meaningful output.”

Here's the most relevant passage from Turing’s 1947 lecture:

“I have spent a considerable time in this lecture on this question of memory, because I believe that the provision of proper storage is the key to the problem of the digital computer, and certainly if they are to be persuaded to show any sort of genuine intelligence much larger capacities than are yet available must be provided. In my opinion this problem of making a large memory available at reasonably short notice is much more important than that of doing operations such as multiplication at high speed. Speed is necessary if the machine is to work fast enough for the machine to be commercially valuable, but a large storage capacity is necessary if it is to be capable of anything more than rather trivial operations. The storage capacity is therefore the more fundamental requirement.”

I would argue that the data resulting from the digitization of everything is the essence of “computing,” of why and how high-speed electronic calculators were invented seventy-five years ago and of their transformation over the years into a ubiquitous technology, embedded, for better or worse, in everything we do. This has been a journey from data processing to big data.

As Thomas Haigh and Paul Ceruzzi write in A New History of Modern Computing, “early computers wasted much of their incredibly expensive time waiting for data to arrive from peripherals.” This problem of latency, of efficient access to data, played a crucial role in the computing transformations of subsequent years, but it has been overshadowed by the dynamics of an industry driven by the rapid and reliable advances in processing speeds (so-called “Moore’s Law”). Responding (in the 1980s) to computer vendors telling their customers to upgrade to a new, faster processor, computer storage professionals wryly noted “they are all waiting [for data] at the same speed.”

The rapidly declining cost of computer memory (driven by the scale economies of personal computers) helped address latency issues in the 1990s, just at the time business executives started to use the data captured by their computer systems not only for accounting and other internal administrative processes. They stopped deleting the data, instead storing it for longer periods of time, and started sharing it among different business functions and with their suppliers and customers. Most important, they started analyzing the data to improve various business activities, customer relations, and decision-making. “Data mining” became the 1990s new big thing, as the business challenge shifted from “how to get the data quickly?” to ”how to make sense of the data?”

A bigger thing that decade, with much larger implications for data and its uses—and for the definition of “computing”—was the invention of the Web and the companies it begat. Having been born digital, living the online life, meant not only excelling in hardware and software development (and building their own “clouds”), but also innovating in the collection and analysis of the mountains of data produced by the online activities of millions of individuals and enterprises. In the last decade or so, the cutting edge of “computing” became “big data” and “AI” (more accurately labeled “deep learning”), the sophisticated statistical analysis of lots and lots of data, and the merging of software development and data mining skills (“data science”).

Data has taken over from hardware and software as the center of everything “computing,” the lifeblood of tech companies. And increasingly, the lifeblood of any type of business.

As Turing said in 1947, “the provision of proper storage is the key to the problem of the digital computer.”